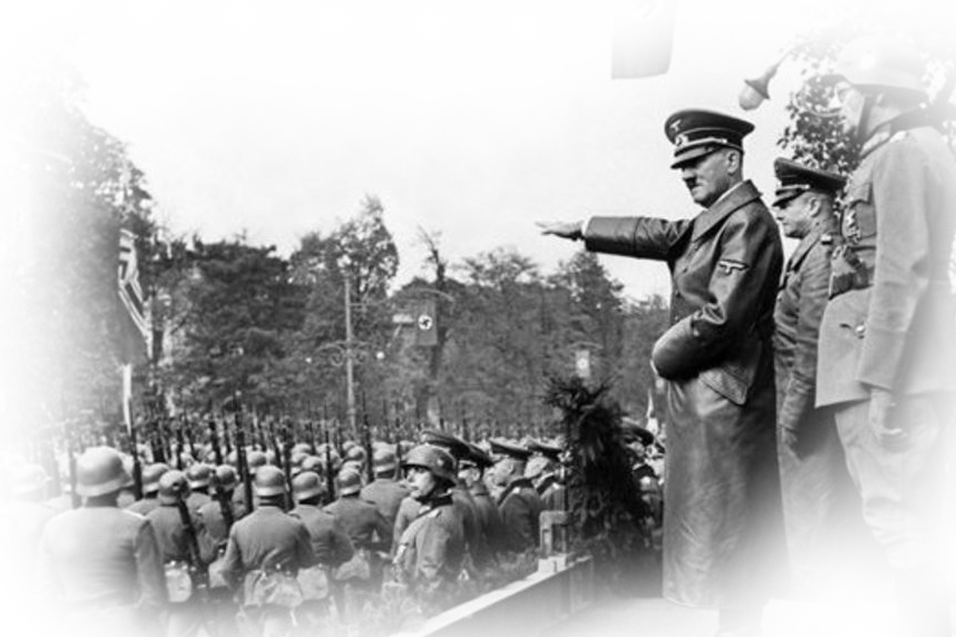

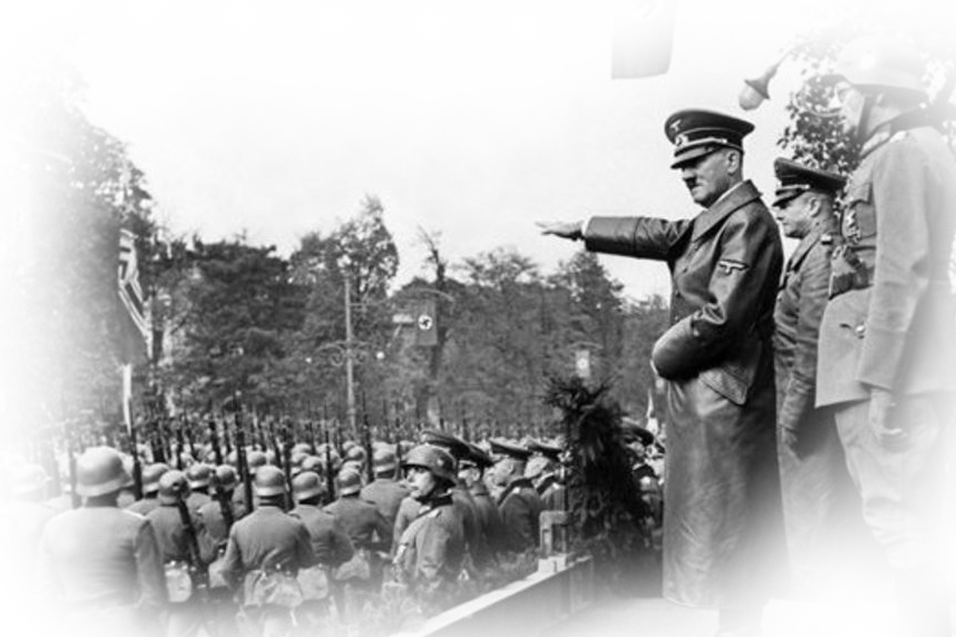

The German conquest of Poland in September 1939 was the first demonstration in war of the new theory of high-speed armoured warfare that had been adopted by the Germans when their rearmament began. Poland was a country all too well suited for such a demonstration. Its frontiers were immensely long—about 3,500 miles in all; and the stretch of 1,250 miles adjoining German territory had recently been extended to 1,750 miles in all by the German occupation of Bohemia-Moravia and of Slovakia, so that Poland’s southern flank became exposed to invasion—as the northern flank, facing East Prussia, already was. Western Poland had become a huge salient that lay between Germany’s jaws.

![]()

It would have been wiser for the Polish Army to assemble farther back, behind the natural defense line formed by the Vistula and San rivers, but that would have entailed the abandonment of some of the most valuable western parts of the country, including the Silesian coalfields and most of the main industrial zone, which lay west of the river barrier. The economic argument for delaying the German approach to the main industrial zone was heavily reinforced by Polish national pride and military overconfidence.

![]()

It would have been wiser for the Polish Army to assemble farther back, behind the natural defense line formed by the Vistula and San rivers, but that would have entailed the abandonment of some of the most valuable western parts of the country, including the Silesian coalfields and most of the main industrial zone, which lay west of the river barrier. The economic argument for delaying the German approach to the main industrial zone was heavily reinforced by Polish national pride and military overconfidence.

October 10. Profiting quickly from its understanding with Germany, the U.S.S.R. on October 10, 1939, constrained Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to admit Soviet garrisons onto their territories. Approached with similar demands, Finland refused to comply, even though the U.S.S.R. offered territorial compensation elsewhere for the cessions that it was requiring for its own strategic reasons. Finland’s armed forces amounted to about 200,000 troops in 10 divisions. The Soviets eventually brought about 70 divisions (about 1,000,000 men) to bear in their attack on Finland, along with about 1,000 tanks. Soviet troops attacked Finland on November 30, 1939.

![]()

Invasion of the Soviet Union, 1941

For the campaign against the Soviet Union, the Germans allotted almost 150 divisions containing a total of about 3,000,000 men. Among these were 19 panzer divisions, and in total the “Barbarossa” force had about 3,000 tanks, 7,000 artillery pieces, and 2,500 aircraft. It was in effect the largest and most powerful invasion force in human history. The Germans’ strength was further increased by more than 30 divisions of Finnish and Romanian troops.

![]()

The Soviet Union had twice or perhaps three times the number of both tanks and aircraft as the Germans had, but their aircraft were mostly obsolete. The Soviet tanks were about equal to those of the Germans, however. A greater hindrance to Hitler’s chances of victory was that the German intelligence service underestimated the troop reserves that Stalin could bring up from the depths of the U.S.S.R. The Germans correctly estimated that there were about 150 divisions in the western parts of the U.S.S.R. and reckoned that 50 more might be produced. But the Soviets actually brought up more than 200 fresh divisions by the middle of August, making a total of 360. The consequence was that, though the Germans succeeded in shattering the original Soviet armies by superior technique, they then found their path blocked by fresh ones. The effects of the miscalculations were increased because much of August was wasted while Hitler and his advisers were having long arguments as to what course they should follow after their initial victories. Another factor in the Germans’ calculations was purely political, though no less mistaken; they believed that within three to six months of their invasion, the Soviet regime would collapse from lack of domestic support.

For the campaign against the Soviet Union, the Germans allotted almost 150 divisions containing a total of about 3,000,000 men. Among these were 19 panzer divisions, and in total the “Barbarossa” force had about 3,000 tanks, 7,000 artillery pieces, and 2,500 aircraft. It was in effect the largest and most powerful invasion force in human history. The Germans’ strength was further increased by more than 30 divisions of Finnish and Romanian troops.

The Soviet Union had twice or perhaps three times the number of both tanks and aircraft as the Germans had, but their aircraft were mostly obsolete. The Soviet tanks were about equal to those of the Germans, however. A greater hindrance to Hitler’s chances of victory was that the German intelligence service underestimated the troop reserves that Stalin could bring up from the depths of the U.S.S.R. The Germans correctly estimated that there were about 150 divisions in the western parts of the U.S.S.R. and reckoned that 50 more might be produced. But the Soviets actually brought up more than 200 fresh divisions by the middle of August, making a total of 360. The consequence was that, though the Germans succeeded in shattering the original Soviet armies by superior technique, they then found their path blocked by fresh ones. The effects of the miscalculations were increased because much of August was wasted while Hitler and his advisers were having long arguments as to what course they should follow after their initial victories. Another factor in the Germans’ calculations was purely political, though no less mistaken; they believed that within three to six months of their invasion, the Soviet regime would collapse from lack of domestic support.

October 2. Bock’s renewed advance on Moscow began on October 2, 1941. Its prospects looked bright when Bock’s armies brought off a great encirclement around Vyazma, where 600,000 more Soviet troops were captured. That left the Germans momentarily with an almost clear path to Moscow. But the Vyazma battle had not been completed until late October; the German troops were tired, the country became a morass as the weather got worse, and fresh Soviet forces appeared in the path as they plodded slowly forward. Some of the German generals wanted to break off the offensive and to take up a suitable winter line. But Bock wanted to press on, believing that the Soviets were on the verge of collapse, while Brauchitsch and Halder tended to agree with his view. As that also accorded with Hitler’s desire, he made no objection. The temptation of Moscow, now so close in front of their eyes, was too great for any of the topmost leaders to resist. On December 2 a further effort was launched, and some German detachments penetrated into the suburbs of Moscow; but the advance as a whole was held up in the forests covering the capital. The stemming of this last phase of the great German offensive was partly due to the effects of the Russian winter, whose subzero temperatures were the most severe in several decades. In October and November a wave of frostbite cases had decimated the ill-clad German troops, for whom provisions of winter clothing had not been made, while the icy cold paralyzed the Germans’ mechanized transport, tanks, artillery, and aircraft. The Soviets, by contrast, were well clad and tended to fight more effectively in winter than did the Germans. By this time German casualties had mounted to levels that were unheard of in the campaigns against France and the Balkans; by November the Germans had suffered about 730,000 casualties.

October 2. Bock’s renewed advance on Moscow began on October 2, 1941. Its prospects looked bright when Bock’s armies brought off a great encirclement around Vyazma, where 600,000 more Soviet troops were captured. That left the Germans momentarily with an almost clear path to Moscow. But the Vyazma battle had not been completed until late October; the German troops were tired, the country became a morass as the weather got worse, and fresh Soviet forces appeared in the path as they plodded slowly forward. Some of the German generals wanted to break off the offensive and to take up a suitable winter line. But Bock wanted to press on, believing that the Soviets were on the verge of collapse, while Brauchitsch and Halder tended to agree with his view. As that also accorded with Hitler’s desire, he made no objection. The temptation of Moscow, now so close in front of their eyes, was too great for any of the topmost leaders to resist. On December 2 a further effort was launched, and some German detachments penetrated into the suburbs of Moscow; but the advance as a whole was held up in the forests covering the capital. The stemming of this last phase of the great German offensive was partly due to the effects of the Russian winter, whose subzero temperatures were the most severe in several decades. In October and November a wave of frostbite cases had decimated the ill-clad German troops, for whom provisions of winter clothing had not been made, while the icy cold paralyzed the Germans’ mechanized transport, tanks, artillery, and aircraft. The Soviets, by contrast, were well clad and tended to fight more effectively in winter than did the Germans. By this time German casualties had mounted to levels that were unheard of in the campaigns against France and the Balkans; by November the Germans had suffered about 730,000 casualties. November 22. In the south, Kleist had already reached Rostov-on-Don, gateway to the Caucasus, on November 22, but had exhausted his tanks’ fuel in doing so. Rundstedt, seeing the place to be untenable, wanted to evacuate it but was overruled by Hitler. A Soviet counteroffensive recaptured Rostov on November 28, and Rundstedt was relieved of his command four days later. The Germans, however, managed to establish a front on the Mius River—as Rundstedt had recommended.

November 22. In the south, Kleist had already reached Rostov-on-Don, gateway to the Caucasus, on November 22, but had exhausted his tanks’ fuel in doing so. Rundstedt, seeing the place to be untenable, wanted to evacuate it but was overruled by Hitler. A Soviet counteroffensive recaptured Rostov on November 28, and Rundstedt was relieved of his command four days later. The Germans, however, managed to establish a front on the Mius River—as Rundstedt had recommended.In the south, Kleist had already reached Rostov-on-Don, gateway to the Caucasus, on November 22, but had exhausted his tanks’ fuel in doing so. Rundstedt, seeing the place to be untenable, wanted to evacuate it but was overruled by Hitler. A Soviet counteroffensive recaptured Rostov on November 28, and Rundstedt was relieved of his command four days later. The Germans, however, managed to establish a front on the Mius River—as Rundstedt had recommended.

In the south, Kleist had already reached Rostov-on-Don, gateway to the Caucasus, on November 22, but had exhausted his tanks’ fuel in doing so. Rundstedt, seeing the place to be untenable, wanted to evacuate it but was overruled by Hitler. A Soviet counteroffensive recaptured Rostov on November 28, and Rundstedt was relieved of his command four days later. The Germans, however, managed to establish a front on the Mius River—as Rundstedt had recommended.

November 5

The German 4th Panzer Army, after being diverted to the south to help Kleist’s attack on Rostov late in July 1942 (see above The Germans’ summer offensive in southern Russia, 1942), was redirected toward Stalingrad a fortnight later. Stalingrad was a large industrial city producing armaments and tractors; it stretched for 30 miles along the banks of the Volga River. By the end of August the 4th Army’s northeastward advance against the city was converging with the eastward advance of the 6th Army, under General Friedrich Paulus, with 330,000 of the German Army’s finest troops. The Red Army, however, put up the most determined resistance, yielding ground only very slowly and at a high cost as the 6th Army approached Stalingrad. On August 23 a German spearhead penetrated the city’s northern suburbs, and the Luftwaffe rained incendiary bombs that destroyed most of the city’s wooden housing. The Soviet 62nd Army was pushed back into Stalingrad proper, where, under the command of General Vasily I. Chuikov, it made a determined stand. Meanwhile, the Germans’ concentration on Stalingrad was increasingly draining reserves from their flank cover, which was already strained by having to stretch so far—400 miles on the left (north), as far as Voronezh, 400 again on the right (south), as far as the Terek River. By mid-September the Germans had pushed the Soviet forces in Stalingrad back until the latter occupied only a nine-mile-long strip of the city along the Volga, and this strip was only two or three miles wide. The Soviets had to supply their troops by barge and boat across the Volga from the other bank. At this point Stalingrad became the scene of some of the fiercest and most concentrated fighting of the war; streets, blocks, and individual buildings were fought over by many small units of troops and often changed hands again and again. The city’s remaining buildings were pounded into rubble by the unrelenting close combat. The most critical moment came on October 14, when the Soviet defenders had their backs so close to the Volga that the few remaining supply crossings of the river came under German machine-gun fire. The Germans, however, were growing dispirited by heavy losses, by fatigue, and by the approach of winter.

![]()

The German 4th Panzer Army, after being diverted to the south to help Kleist’s attack on Rostov late in July 1942 (see above The Germans’ summer offensive in southern Russia, 1942), was redirected toward Stalingrad a fortnight later. Stalingrad was a large industrial city producing armaments and tractors; it stretched for 30 miles along the banks of the Volga River. By the end of August the 4th Army’s northeastward advance against the city was converging with the eastward advance of the 6th Army, under General Friedrich Paulus, with 330,000 of the German Army’s finest troops. The Red Army, however, put up the most determined resistance, yielding ground only very slowly and at a high cost as the 6th Army approached Stalingrad. On August 23 a German spearhead penetrated the city’s northern suburbs, and the Luftwaffe rained incendiary bombs that destroyed most of the city’s wooden housing. The Soviet 62nd Army was pushed back into Stalingrad proper, where, under the command of General Vasily I. Chuikov, it made a determined stand. Meanwhile, the Germans’ concentration on Stalingrad was increasingly draining reserves from their flank cover, which was already strained by having to stretch so far—400 miles on the left (north), as far as Voronezh, 400 again on the right (south), as far as the Terek River. By mid-September the Germans had pushed the Soviet forces in Stalingrad back until the latter occupied only a nine-mile-long strip of the city along the Volga, and this strip was only two or three miles wide. The Soviets had to supply their troops by barge and boat across the Volga from the other bank. At this point Stalingrad became the scene of some of the fiercest and most concentrated fighting of the war; streets, blocks, and individual buildings were fought over by many small units of troops and often changed hands again and again. The city’s remaining buildings were pounded into rubble by the unrelenting close combat. The most critical moment came on October 14, when the Soviet defenders had their backs so close to the Volga that the few remaining supply crossings of the river came under German machine-gun fire. The Germans, however, were growing dispirited by heavy losses, by fatigue, and by the approach of winter.

November 19. A huge Soviet counteroffensive, planned by generals G.K. Zhukov, A.M. Vasilevsky, and Nikolay Nikolayevich Voronov, was launched on Nov. 19–20, 1942, in two spearheads, north and south of the German salient whose tip was at Stalingrad. The twin pincers of this counteroffensive struck the flanks of the German salient at points about 50 miles north and 50 miles south of Stalingrad and were designed to isolate the 250,000 remaining men of the German 6th and 4th armies in the city. The attacks quickly penetrated deep into the flanks, and by November 23 the two prongs of the attack had linked up about 60 miles west of Stalingrad; the encirclement of the two German armies in Stalingrad was complete. The German high command urged Hitler to allow Paulus and his forces to break out of the encirclement and rejoin the main German forces west of the city, but Hitler would not contemplate a retreat from the Volga River and ordered Paulus to “stand and fight.” With winter setting in and food and medical supplies dwindling, Paulus’ forces grew weaker. In mid-December Hitler allowed one of the most talented German commanders, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, to form a special army corps to rescue Paulus’ forces by fighting its way eastward, but Hitler refused to let Paulus fight his way westward at the same time in order to link up with Manstein. This fatal decision doomed Paulus’ forces, since the main German forces now simply lacked the reserves needed to break through the Soviet encirclement singlehandedly. Hitler exhorted the trapped German forces to fight to the death, but on Jan. 31, 1943, Paulus surrendered; 91,000 frozen, starving men (all that was left of the 6th and 4th armies) and 24 generals surrendered with him.

![]()

January 20. Besides being the greatest battle of the war, Stalingrad proved to be the turning point of the military struggle between Germany and the Soviet Union. The battle used up precious German reserves, destroyed two entire armies, and humiliated the prestigious German war machine. It also marked the increasing skill and professionalism of a group of younger Soviet generals who had emerged as capable commanders, chief among whom was Zhukov.

![]()

1943 January 11

The attacks quickly penetrated deep into the flanks, and by November 23 the two prongs of the attack had linked up about 60 miles west of Stalingrad; the encirclement of the two German armies in Stalingrad was complete. The German high command urged Hitler to allow Paulus and his forces to break out of the encirclement and rejoin the main German forces west of the city, but Hitler would not contemplate a retreat from the Volga River and ordered Paulus to “stand and fight.” With winter setting in and food and medical supplies dwindling, Paulus’ forces grew weaker.

![]()

The attacks quickly penetrated deep into the flanks, and by November 23 the two prongs of the attack had linked up about 60 miles west of Stalingrad; the encirclement of the two German armies in Stalingrad was complete. The German high command urged Hitler to allow Paulus and his forces to break out of the encirclement and rejoin the main German forces west of the city, but Hitler would not contemplate a retreat from the Volga River and ordered Paulus to “stand and fight.” With winter setting in and food and medical supplies dwindling, Paulus’ forces grew weaker.

June 17

Paulus and his forces to break out of the encirclement and rejoin the main German forces west of the city, but Hitler would not contemplate a retreat from the Volga River and ordered Paulus to “stand and fight.” With winter setting in and food and medical supplies dwindling, Paulus’ forces grew weaker.

![]()

In mid-December Hitler allowed one of the most talented German commanders, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, to form a special army corps to rescue Paulus’ forces by fighting its way eastward, but Hitler refused to let Paulus fight his way westward at the same time in order to link up with Manstein. This fatal decision doomed Paulus’ forces, since the main German forces now simply lacked the reserves needed to break through the Soviet encirclement singlehandedly. Hitler exhorted the trapped German forces to fight to the death, but on Jan. 31, 1943, Paulus surrendered; 91,000 frozen, starving men (all that was left of the 6th and 4th armies) and 24 generals surrendered with him.

![]()

![]()

Paulus and his forces to break out of the encirclement and rejoin the main German forces west of the city, but Hitler would not contemplate a retreat from the Volga River and ordered Paulus to “stand and fight.” With winter setting in and food and medical supplies dwindling, Paulus’ forces grew weaker.

In mid-December Hitler allowed one of the most talented German commanders, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, to form a special army corps to rescue Paulus’ forces by fighting its way eastward, but Hitler refused to let Paulus fight his way westward at the same time in order to link up with Manstein. This fatal decision doomed Paulus’ forces, since the main German forces now simply lacked the reserves needed to break through the Soviet encirclement singlehandedly. Hitler exhorted the trapped German forces to fight to the death, but on Jan. 31, 1943, Paulus surrendered; 91,000 frozen, starving men (all that was left of the 6th and 4th armies) and 24 generals surrendered with him.